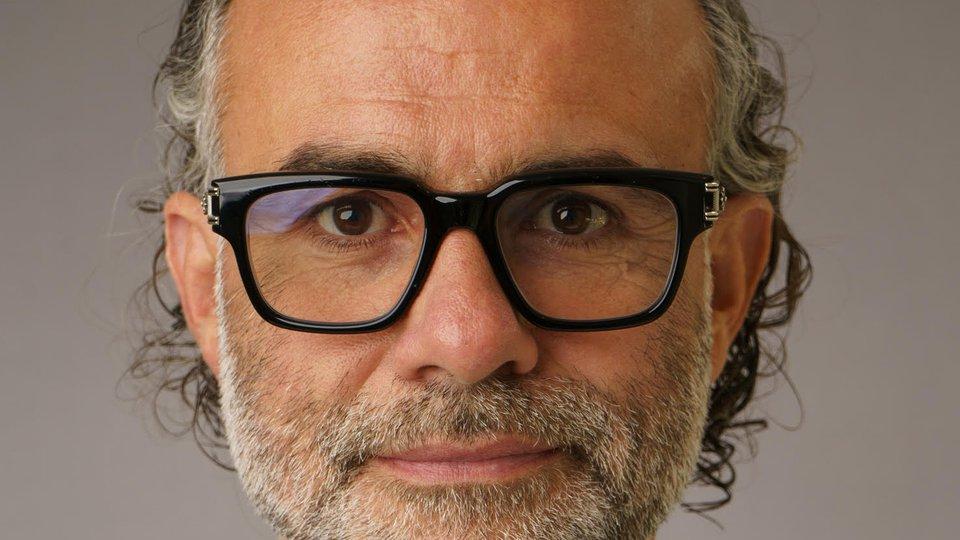

Piaget CEO Philippe Léopold-Metzger shares his aspirations for the 141-year old watch brand and talks future, challenges and the critical importance of fostering skills for the next generation.

Interview: Philippe Léopold-Metzger, CEO, Piaget

Over the last decade, collaborations between luxury brands and contemporary artists have gone beyond mere artistic partnerships towards a new kind of luxury branding.

PARIS – Art and fashion have always developed side by side, for fashion, like art, often gives visual expression to the cultural zeitgeist. During the 1920s, Salvador Dalí created dresses for Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiapparelli. In the 1930s, Ferragamo’s shoes commissioned designs for advertisements from Futurist painter Lucio Venna, while Gianni Versace commissioned works from artists such as Alighiero Boetti and Roy Lichtenstein for the launch of his collections. Yves Saint Laurent’s vast art collection, recently auctioned at Christie’s in Paris, testified to his great love of art and revealed the influence of a variety of artists on his own designs.

In the 1980s, relationships between luxury brands and artists were advanced when Alain Dominique Perrin created the Fondation Cartier. In the Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain, a book marking the foundation’s 20th anniversary, Perrin says he makes “a connection between all the different sorts of arts, and luxury goods are a kind of art. Luxury goods are handicrafts of art, applied art.”

The Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemparain building in Paris

Piaget CEO Philippe Léopold-Metzger shares his aspirations for the 141-year old watch brand and talks future, challenges and the critical importance of fostering skills for the next generation.

Piaget CEO Philippe Léopold-Metzger shares his aspirations for the 141-year old watch brand and talks future, challenges and the critical importance of fostering skills for the next generation.

As a company founded in the manufacturing of watch movements, it’s no surprise that for Piaget – and the man at its helm – the devil is in the details.

Léopold-Metzger speaks with a great affinity for the brand and the quality of the products Piaget produces, and he is fiercely proud of its heritage and dedication to the craft of watch movements, timepieces and, most recently, high jewellery.

“You have a lot of different entrants which have no legitimacy whatsoever. They have money, so that they can to some extent buy awareness and hence in the minds of people, maybe ‘legitimacy’, but historically, it is older brands like Piaget which have been in business for more than 140 years and which really have the heritage behind them,” he says.

Piaget’s latest high jewellery collection, ‘Secrets & Lights’, was revealed just weeks ago during the haute couture shows in Paris and throughout the thread of this exclusive interview, it becomes clear that this growing sector of the business is to be a beacon for expansion in the future.

“High jewellery, in particular, today is on fire, because for people high jewellery has become an investment,” he says.

More so when pieces, such as Piaget’s, are crafted to perfection by skilled craftsmen around the world and laden with cushion-cut emeralds, marquise-cut blue, brilliant-cut diamonds, feathers and rubies.

But again, it’s not the quantity which draws Léopold-Metzger’s attestation, but the quality and craftsmanship behind each creation, which is an essential pillar of the Piaget brand and a high priority where he is concerned.

“Here at Piaget, we are very active in fostering these skills. We are probably one of the most involved companies in sponsoring talent. Now, everyone has joined and all the brands under Richemont sponsor. But we were the first,” he explains.

“We also have a lot of apprentices, so we are actively working to make sure that these skills can be passed from one generation to the other.”

This sense of continuity is also something which is mirrored in Léopold-Metzger’s professional career and, likely, part of what makes him such a fortuitous fit for a brand steeped in 141 years of rich history – indeed, since his entry into the luxury jewellery sphere via the Cartier brand in Paris in 1981, through to his move to Piaget in 1992 and his appointment as the head of the brand in 1996 – he’s never once left the inner circle of the extended family that is Cartier-Vendome-Richemont.

“ You have a lot of different entrants which have no legitimacy whatsoever ”

How is Piaget differentiating itself in the jewellery and watch world now that you have so many different new entrants like Louis Vuitton and other megabrands coming in?

Well, as you said, they are new entrants, whereas we are very old family business that started 141 years ago now. So, we have one thing that no other brand has – the longest legitimacy and expertise, both in the watch business and the movement business and also, in jewellery. We started doing movements – that was the root of the company. Then we started with jewellery craft in gold in the early ’60s.

We’ve been doing the jewellery now for about 55 years and the watch side for 141. You’re not going to find anyone that has such a long experience in both.

Some, such as Cartier, obviously started much more on the jewellery side, while in the last few years they’ve been developing watches. Likewise, we now see brands that were initially watchmakers, which now also develop jewellery.

Then you have a lot of different entrants which have no legitimacy whatsoever. They have money, so that they can to some extent buy awareness and hence in the minds of people, maybe legitimacy, but historically, it is older brands like Piaget which have been in business for more than 140 years and which really have the heritage behind them.

The other thing, which is specific for us, is that we only do watches and jewellery. We do have collections which are quite wide, but we are not going to do watches or pants, or leather or perfume. We are very focused on what we are good at and, therefore, truly legitimate.

“ We are exclusive in the sense that we want to master everything we do ”

Some other brands, such as Mondaine, and Cartier, have now gone on and diversified into leather and different accessories – is that something that Piaget would ever consider?

No, we’re not going to do that. What we are trying to do, for example on the jewellery side, is provide a wider offering.

What we’ve been focusing in the last couple months, for example, is the re-launch of a ring, which as part of a collection we had introduced 25 years ago – called ‘Possession’. It’s a ring within a ring, and we have been very focused on the pricing. So, essentially, we are busy trying to increase the volume of people that can have access to the brand.

It’s interesting, because Piaget also has something which is very, very rare. We are exclusive in the sense that most of what we do, we do ourselves, and therefore, for example, on the watch side, the access price through the range is quite high – for men, it starts at 15,000 Euro. For women, it’s around 7,000 Euro.

Possession also starts at 7,000 Euros. But for jewellery, generally, the entry barrier is lower.

Yet, we are not exclusive in the sense that we are arrogant. We are exclusive in the sense that we want to master everything we do, and producing something in limited quantities for us is an asset more than anything else.

Now though, it’s true that in some areas we want to expand the number of clients a little bit, and jewellery is perfect for that. I was looking at the numbers, for example, for the first seven days of July in our stores – we sold five pieces of jewellery for each watch sold. Since the beginning of the year, the number of people buying is developing fast. Which is important.

Again, in the jewellery we start at 1000 Euros, but we have now developed Possession. This is really a key collection for us. It is the second jewellery collection we’ve done for this year, and we have quite extensive collections.

But in terms of expansion, today, we feel that there is a lot of business also on the very top end on the very high jewellery side.

Secrets & Lights collection by Piaget

You mentioned pricing. Given the fluctuations in currency – with the Swiss Franc for example, and now the Japanese Yen which getting stronger, what are the challenges in pricing your products?

Well, it’s always difficult with watches because the currencies are changing. I think now we have really implemented – and I would say in a much more drastic way than most other groups – something which is basically a type of fair pricing.

Which means that if you take away the VAT, which can differ from one country to another, the idea is that wherever you are, the difference is not likely to be larger than 10%. This is what we’re aiming for.

We will keep adjusting if we need to though, so if tomorrow the dollar gets weak, then we would probably increase the price. It’s a bit like having a currency that is moving between two barriers, and you keep a middle ground, and if they change, you re-adjust.

“ Today, if you look at the Richemont Group, we are where we belong ”

Do you think because consumers are so global now though, that it is something that you can absorb in a sense?

Definitely. But again, for us, it may not be the same. Because, if you buy a piece of jewellery for 1000 Euros for example, you may not go through the same thinking than if you buy a watch at 50,000 Euros. Today, clients can very easily have a price comparison, because we put pricing on the site, so they have information. But in any case, they know exactly what they are looking at.

So, for us, pricing has become something which is key, and something our clients care about. They come with a calculator in their phone. You see them from time to time. When they come in, they already know what they want – and they know exactly what price it’s going to be the price in Japan or in China, and they compare.

“ We have our limits when it comes to mass production and lower pricing ”

Mass customisation has been a rising trend lately and some brands, like Burberry for example, have introduced some more entry level prices. Is this something that you think you might one day start bringing into the jewellery side?

No, I don’t think so. Today, if you look at the Richemont Group, we are where we belong. We have some nice brands between Cartier, Van Cleef, and Piaget, and I think the success of all the brands has been that we have been able to simultaneously develop small-sized jewellery, medium jewellery and also, high jewellery.

High jewellery, in particular, today is on fire, because for people high jewellery has become an investment.

Today, if you come out with an exceptional ring, people are more likely to invest in it, because it’s sort of a great synergy between the joy of wearing the product, and also the fact that you know that the price of the stones within it has been growing gradually for the last few decades. Honestly, it’s a good investment.

In jewellery, also, we have our limits when it comes to mass production and lower pricing. The standard of the product needs to be great, and this is the problem of luxury. We are against mass production. Our business is much more about working with more limited quantities, and this is much more our business model.

A hand-crafted piece from the collection: ‘Secrets & Lights’

Speaking of quality – there had been talk a few years ago about skill shortages, in terms of craftsmanship. Now that everybody is so focused on digital and a lot of young people are going into this field, do you foresee challenges in the future to attract the next generation to make these beautiful, handmade products?

It’s a very good question, and yes, that is something of concern. But here at Piaget, we are very active in fostering these skills.

We are probably one of the most involved companies in sponsoring talent, and there is a very big jewellery school in Paris, which we have sponsored to that end. We started about 10 or 15 years ago, I think, now everyone has joined and all the brands under Richemont sponsor. Cartier, Van Cleef, every brand. But we were the first.

We also have a lot of apprentices, so we are actively working to make sure that these skills can be passed from one generation to the other. As a group, we are also working very actively on that subject, and there are going to be some quite interesting things coming out of that later at the group level.

Also we have for example something in the group which is called a creative academy, which is a one-year program in Milan, where we basically take students that have done sort of a design degree, and provide them with both work and projects. While there, they also have access to a lot of CEOs, all the CEOs of Richemont, but also many CEOs from competing groups.

So, again, with that initiative, we try to stimulate their skills in designing, and then we hire them.

Most of them find very easy these jobs in companies, and we feel that it’s an area of social responsibility for us, really, to train these young people, and at the same time, we make sure that we have the skills necessary to continue at our level of quality.

“ We are probably one of the most involved companies in sponsoring talent ”

What we do also, which is very interesting, is work with a lot of different artisans across the world. We have long-term contracts with them, and what we do is we choose fantastic artists that may not come and work for us, but we forge a partnership with them, and they’ve gone on to work on some incredible things from there.

For instance, we have a mosaician who does glass mosaics – during the day, he is a mosaician at the Vatican – and the dial of a watch he’s made is composed of 5,000 little mosaic pieces. We then have a German artist, whose skill is engraving gold, so we’ll fold that into the collections too. This is something that we are doing continuously, and we are finding new skills all the time.

We are currently working with them to produce ‘Secrets & Lights: A Mythical Journey Number Two’ – a collection of 38 watches which will be launching in Hong Kong in September. Then the whole collection of watch and jewellery is really going to be marketed for the public starting in November.

When we do the event with all the VIPs, we are going to bring five of those artisans, who are going to explain their skills. In other words, it’s not only that we want to stimulate their creativity, but we also want to give them a lot of exposure, and that’s is important, because we consider them incredible artists.

“ Sometimes you realise you have opened stores in some cities in the past, which today, you just cannot justify ”

You mentioned the importance of limiting product to protect the exclusivity earlier. Piaget now has in the range of 100 stores globally – but will there be a point where you’ll stop opening stores to protect the exclusivity?

No, because we are also working on the distribution. We have been reducing the wholesale distribution that we have, and focusing the wholesale distribution much more on watches. But in most countries in the world, in the future, we will only sell the jewellery in the stores.

That will allow us also to refocus more on watches within the traditional watch retailers. Sometimes, we have so many products that everything gets lost. So, the idea for us is to continue to develop our wholesale business as the best watch retailers in the world, and to concentrate more of the jewellery distribution in stores. We need to have visibility.

For example, we are opening in Milan. It’s our first store in Italy. It’s a beautiful store, 250 square meters, and we are also looking at a project in Madrid where we don’t have a store yet.

We are also actively looking outside Asia. In Asia, we already have pretty good coverage, yet still, we are going to open a store in China in Wuhan where we don’t have a store, so we are constantly on the hunt for new locations.

But we’re not going to go to 250 stores. I think probably, one day, we may be at 130 or 150, and then we’ll probably look to close the least productive locations, because when you develop, sometimes you realise you have opened stores in some cities in the past, which today, you just cannot justify.

But overall, we are going to concentrate on strengthening our ties with the better watch retailers, and then we will have the number of boutiques which is necessary.

Piaget boutique, Hong Kong

Now that you have Yoox and NET-A-PORTER within the Richemont Group, what role do you think that e-commerce will play for Piaget?

We think that e-commerce will play a significant role, because this is the way things go. It was very interesting, because we had a meeting maybe seven or eight years ago where we talked about e-commerce and Richemont brands and our owner said: "You have to look at it”. Back then we were very, very cautious.

But this is why we probably bought NET-A-PORTER, because it gave us exposure to e-commerce. We’re leaving each brand to judge how they want to do it themselves. We are active in e-commerce in the States, across Europe in most of countries. We are going to start e-commerce later this year in China, and in Japan, where we don’t have e-commerce, and work on phone sales, we are looking at it.

We think it’s going to be an effective way of reaching clients. But we don’t do e-commerce for the sake of selling. We generally start by first trying to make as good a site as we can, and then having a contact center. We started in France very early on. Now we’re active with contact centers in most places.

Then again, some people love to buy, and they have the culture of buying online, and it’s something that we have nothing against, but we still like the fact that people can come to a store and look at the product.

“ One of the biggest challenges is to make sure that the brand remains unique ”

Looking ahead, what do you foresee as the biggest challenges Piaget will face in the coming years?

I think one of the biggest challenges is to make sure that the brand remains unique. I think that for a luxury brand to survive, you have to prioritise quality, and creativity, and uniqueness, rather than do big volumes.

I think some brands will disappear because they don’t produce quality products and I think they just don’t value the customer enough. I think you also have to focus a lot on what the consumers really want. You need to be able to do customisation of products, which is again something that we can do.

It is a competitive market though. Today it’s obvious that especially on the jewellery side, more brands are getting better, and hence you have a lot of competition. But competition when you are in the company of great professionals is great, because it increases the attractiveness of the market. So, as long as it’s a very healthy competition, I think it’s going to be great. Good competition means that you have to be one step ahead.

“ You have to be exclusive, but still you have to reach a critical mass ”

I think clients are also increasingly looking for products which are different. So you need to find a niche market. For example, in watches, because you cannot be everything to everyone. You have to make choices.

But in watches, again, our situation is quite interesting, because we have always been known as the jeweller of watchmakers, and obviously we also have a huge story in watchmaking. Working in both fields is not easy, because people may say: "Yes, Piaget is a jewelry brand, I don’t understand why they make timepieces. But I think we did something which was smart, which was going back to our DNA. So at least everywhere we are, we have unique and distinctive products, and I think this is what you need in the future to survive.

Having said that, there is a part of that which is contradictory. You have to be exclusive, but still you have to reach a critical mass. Otherwise you cannot afford to have stores on the key streets in the world, and you cannot advertise. So this is a little bit hard. But you don’t have to be huge, you just have to be big enough.

Otherwise, you are going to lose against fashion brands that are using a lot of their enormous budget to focus on products in which they buy “legitimacy”.

Additional editing by Daniela Aroche, Editorial Director of Luxury Society

For more in our series of conversations with Luxury Leaders, please see our most recent editions as follows:

– In Conversation With Michele Norsa, CEO & Group Managing Director, Salvatore Ferragamo

– In Conversation with Jean-Noël Kapferer, Author Of ‘The Luxury Strategy’

– In Conversation With Mike Flewitt, CEO, McLaren Automotive

Creative Strategist, Digital

Sophie Doran is currently Senior Creative Strategist, Digital at Karla Otto. Prior to this role, she was the Paris-based editor-in-chief of Luxury Society. Prior to joining Luxury Society, Sophie completed her MBA in Melbourne, Australia, with a focus on luxury brand dynamics and leadership, whilst simultaneously working in management roles for several luxury retailers.