Manpower recently released the results of a survey it conducted among 19,000 young people born between 1982 and 1996 in 25 countries. Europa Star’s Serge Maillard analyzes the findings.

“Explosion” Generation: Millennials in the Luxury Workforce

Over the last decade, collaborations between luxury brands and contemporary artists have gone beyond mere artistic partnerships towards a new kind of luxury branding.

PARIS – Art and fashion have always developed side by side, for fashion, like art, often gives visual expression to the cultural zeitgeist. During the 1920s, Salvador Dalí created dresses for Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiapparelli. In the 1930s, Ferragamo’s shoes commissioned designs for advertisements from Futurist painter Lucio Venna, while Gianni Versace commissioned works from artists such as Alighiero Boetti and Roy Lichtenstein for the launch of his collections. Yves Saint Laurent’s vast art collection, recently auctioned at Christie’s in Paris, testified to his great love of art and revealed the influence of a variety of artists on his own designs.

In the 1980s, relationships between luxury brands and artists were advanced when Alain Dominique Perrin created the Fondation Cartier. In the Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain, a book marking the foundation’s 20th anniversary, Perrin says he makes “a connection between all the different sorts of arts, and luxury goods are a kind of art. Luxury goods are handicrafts of art, applied art.”

The Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemparain building in Paris

Manpower recently released the results of a survey it conducted among 19,000 young people born between 1982 and 1996 in 25 countries. Europa Star’s Serge Maillard analyzes the findings.

It paints a picture of a generation whose aspirations differ dramatically from those of the previous generation, who were marked paradoxically by both the idealistic revolutionary spirit of 1968, and by the “loadsamoney” decades that came later. They had been freed from societal conventions, and all sorts of financial, economic and physical barriers had been lifted. The result: that tired old stereotype of the former revolutionary who now drives a sports car, and soothes those occasional pangs of guilt with a bit of retail therapy and a nice new watch.

"The absence of a guilty conscience gives these Millennials more freedom to pursue the ideals their elders abandoned"

Generation Y, on the other hand, has a far more straightforward relationship with career and money. Paradoxically, the absence of a guilty conscience gives these Millennials more freedom to pursue the ideals their elders abandoned: prioritising professional harmony over an obsessive pursuit of financial and professional success; treating their peers the same, whatever their social status; achieving a work-life balance; returning to more conservative values; looking for meaning and creativity; yearning for boundaries, limits, and a more open and friendly environment, at a time when it seems everything has gone out of the window, and nothing is as it was. This generation has moulded itself into a paradox where individualism and resistance to authority have never been stronger (the result of the “social explosion”), but at the same time, the “digital explosion” has fostered an urge to rebuild bonds and (re)connect with their roots.

The tangible results of the attempt to reconcile these contradictory forces are clear from the Manpower study, which shows that acquiring personal skills (73%) is more important to Millennials than building managerial skills (27%). Just 16% are interested in leadership positions, while “working with great people” is far more important for 33%. Three-quarters would be prepared to change employers if they were guaranteed more training opportunities, even at the same salary level (75%). In parallel with this, the idea of managing a team and working your way up the corporate ladder holds less appeal than finding personal satisfaction. Barely 5% identify reaching the top rung of the career ladder as a goal, most preferring the idea of “being their own boss, not being told what to do”. Manpower urges employers to remain open to “alternative ways of working”.

What are the consequences of these attitudes for the watch industry? (and luxury industry more generally)

Let’s look at two of them (there are many more, but this article has physical limitations – and I’m afraid generalisation is one of the inevitable consequences).

As members of the workforce, Millennials, who have at their fingertips a palette of digital tools and countless inspiring figures to emulate, are keen to test the entrepreneurial waters, or to create their own space within a company, while maintaining a connection with their peers. It is no accident, then, that the charismatic CEOs Jean-Claude Biver (TAG Heuer) and Max Büsser (MB&F;) are probably the most visible figures in our industry, given that both in their way have attitudes that will resonate with Generation Y. Mr Biver is known to be a “great guy” – dynamic and rich but not arrogant, and Mr Büsser promises his employees no more and no less than that they will “work with good people in a creative environment”. I rest my case.

As consumers, Generation Y are all over the place, which goes some way to explaining why, as we try to process the vast “explosion” of everything that is safe and familiar, the watch industry seems to have lost its direction. Torn between the authenticity of the local shop and the convenience of online shopping, they are riddled with contradictions that torture and tempt in equal measure. There are few signposts in this vast chaos, where sometimes it looks like those who shout loudest always win, before they are suddenly eclipsed by a newcomer that prides itself on moderation and reason. And so we turn from bling-bling to vintage. XXL machismo is replaced by the understated cool of Mad Men. That’s what happens, when you have a period of unprecedented and rapid technological, social and economic upheaval. In all of this, the Millennials are both executioners and victims, trapped between the previous generation, which lit the fuse, and the future digital natives who will reap the fallout. There’s a French film called “Life is a Long Quiet River." I’m not so sure about the “quiet” part.

Article originally published on Europa Star

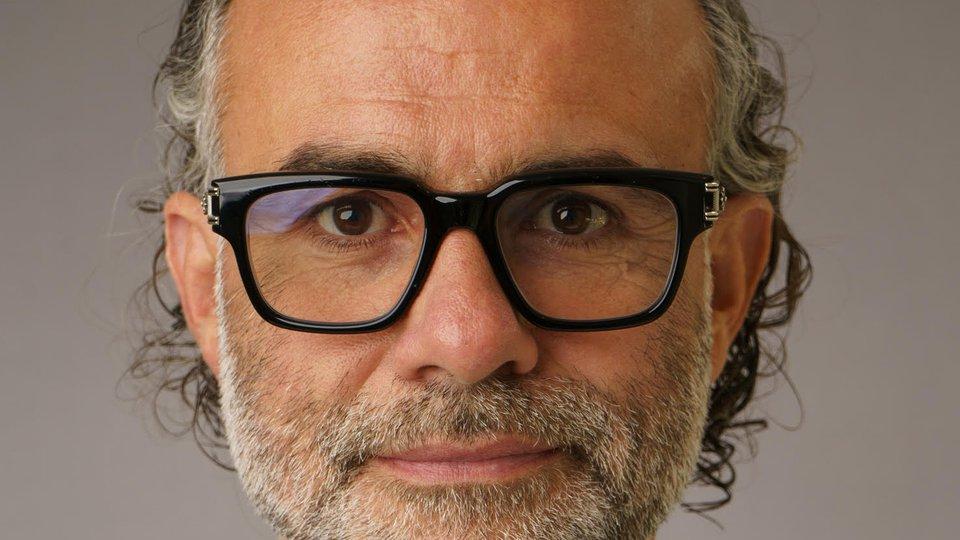

Publisher, Europa Star

Serge is the publisher of Europa Star, a leading independent watch magazine that celebrates 90 years of coverage of the industry. Aimed at both professionals and collectors all around the world and in five languages, it provides unique point of views and exclusive analysis of the evolution of the watch industry.